Most websites you visit nowadays will have you believe they ‘value your privacy’ while presenting you with an annoying popup, containing a wall of small text with a big, green ‘accept all cookies’ button. Contrary to what they want you to believe, such websites take the biscuit with your privacy and break the law en masse. But with the UK Government consulting on reforms and an important Supreme Court judgment in Lloyd v Google, the question is: for how much longer will this be tolerated?

Browsing the web in Europe nowadays is made almost impossible, you’ll hear many people say. Almost every single website requires you to view and navigate an awfully complicated cookie consent modal, usually with many lines of hard-to-read small text and a large green ‘Accept All Cookies’ button at the bottom. The alternative button, usually ‘Manage Preferences’, takes you to another screen with a plethora of sliders, which are usually toggled on by default. At the bottom of this preferences screen, there then tends to be an ‘Accept All Cookies’ and ‘Save Preferences’ button. Only once a visitor has navigated their way through this cookie consent modal, making it almost impossible to reject unnecessary cookies, can they proceed to the website content they were actually looking for. And all this is made out to be for the purpose of ‘respecting your privacy’ and is supposedly the fault of the GDPR and ePrivacy Directive.

However, once you dive deeper into what the GDPR and the ePrivacy Directive actually say, it is clear that this new ‘standard implementation’ for cookie ‘consent’ does not actually constitute valid consent. Consent is required to place any cookies that are not “strictly necessary” (e.g. session authentication cookies) and such unnecessary cookies cannot be placed before consent is given. I will go through some of the top 3 mistakes I come across in cookie ‘consent’ mechanisms that invalidate any supposed consent websites claim to have using some real-world examples. If the appropriate supervisory authorities were to take some basic enforcement action against these common mistakes, the web in Europe would become a much more pleasant, privacy-friendly place to browse – and would actually become compliant with the law.

The Government has put forward proposals to significantly increase the penalties for breaches of PECR, including Regulation 6 regarding cookies, alongside proposals to relax the cookie rules for cookies that constitute a low privacy risk. Furthermore, the Supreme Court’s judgment in Lloyd v Google LLC [2021] contains some crucial comments that could allow data subjects to claim monetary compensation against websites that place cookies on their devices without proper consent.

1 Making it harder to refuse consent than to give it

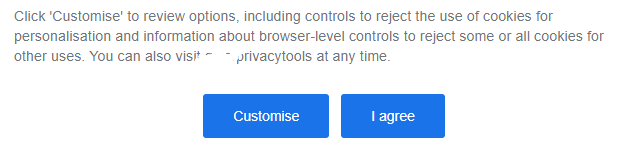

For consent to be valid, amongst other things, users need to be given a binary, equivalent choice between accepting or rejecting that does not disproportionately ‘nudge’ users into giving consent. Here are some examples of where this principle is not applied and the ‘consent’ obtained is thus invalid.

Mechanism A does not give users a binary, equivalent choice. It merely allows users to select ‘I agree’ and ‘Customise’, but it does not allow users to select ‘I do not agree’. If users click ‘Customise, they are taken to a more detailed page tediously requiring them to select ‘No’ for every single unnecessary category before they are able to save and express their wish to not give consent. Thus, because it is harder to refuse consent for all unnecessary cookies, this consent mechanism is unlikely to comply with the GDPR and any obtained ‘consent’ is likely to be invalid.

This could be easily fixed by adding an ‘I do not agree’ button. This would make the consent mechanism have a binary, equivalent choice and be sufficiently granular by allowing users to toggle individual features on the ‘Customise’ page.

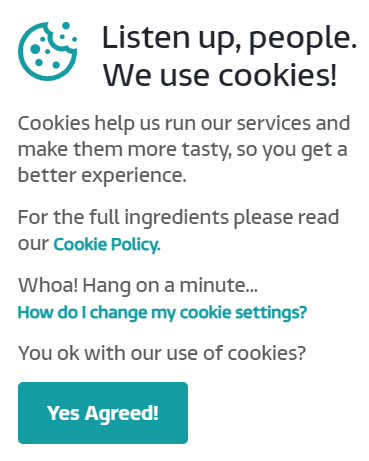

Mechanism B does not actually give users any choice and it is impossible to reject cookies. It is also impossible to proceed to the full website without clicking the ‘Yes Agreed!’ button. As such, the supposed ‘consent’ for cookies this mechanism seeks to obtain is completely invalid. The ‘How do I change my cookie settings?’ page only contains a reference to users being able to block all cookies through their browser settings, but this is clearly also invalid for the purposes of consent and would also block strictly necessary cookies (which are strictly required for the website to function properly).

This can again be easily fixed by adding a ‘No, I do not agree’ button which, if clicked, results in no unnecessary cookies being placed.

Other websites don’t even have an information mechanism at all and just place cookies by default without informing users, or merely show a banner that they ‘use cookies’ without seeking the required consent (continuing to use a website does not constitute consent).

As a rule of thumb, there must be a ‘Disagree’ button wherever an ‘Agree’ button appears and it must be of equivalent prominence and design. Consent mechanism C gets it pretty much right (although it could be argued that the ‘cookie settings’ button to granularly manage consent should be given the same design and prominence as the accept/reject buttons).

2 Using ‘legitimate interests’ and pre-enabled checkboxes/sliders

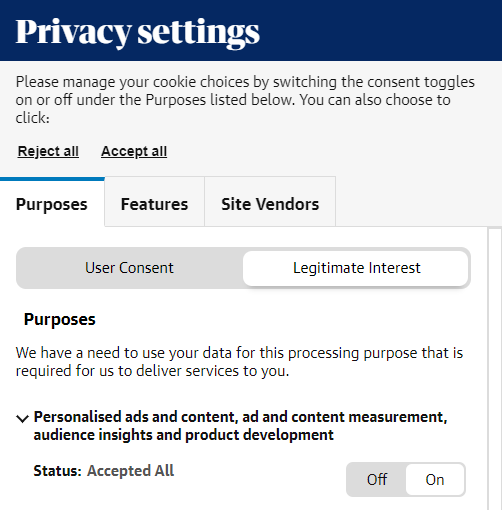

To place cookies that are not strictly necessary, Regulation 6 of PECR clearly provides that GDPR-standard consent must first be obtained. As such, ‘consent’ is usually the only appropriate lawful basis under the GDPR for processing any personal data arising out of unnecessary cookie placement. Despite this, some websites rely on ‘legitimate interests’ to place unnecessary cookies and process personal data associated with them.

Take Mechanism D, for example. In the pre-selected ‘user consent’ tab, it asks for consent to place cookies and to process associated personal data for ‘personalised ads and content’, which are not pre-enabled. But if you select the ‘legitimate interests’ tab, you suddenly see there is a legitimate interests ‘personalised ads and content’ option that is pre-enabled to ‘On’. This is incredibly underhanded, as the user is effectively tricked into clicking ‘Save and close’ as they are initially only presented with the ‘user consent’ tab with all such options disabled.

For consent to be valid, it must be a clear, unambiguous, affirmative action. The GDPR recitals clarify that pre-enabled checkboxes and similar elements such as sliders cannot constitute valid consent. Indeed, pre-enabled checkboxes would constitute an indication that ‘legitimate interests’ is being relied upon and users can effectively object to the processing by unchecking the checkbox.

For consent to be valid, any checkboxes or similar elements must be off by default.

3 Not respecting the settings and not allowing them to be easily changed

Rather obviously, once the user has confirmed their settings, they should be respected. In other words, only cookies that the user has consented to may be placed (unless the cookies are strictly necessary). All too often, this is not the case and cookies that the user has not consented to are be placed anyway. You can easily check this using the cookie storage list of your browser and the publicly available cookie databases.

Furthermore, the user must easily be able to change their cookie consent settings at any time. This is often not facilitated, with the option either not existing at all or buried deep in a wall of text. There should simply be a ‘cookie settings’ link added to the website footer, or, at the very least, a clear button displayed at the top of the cookie/privacy policy pages. This should then ordinarily reopen the consent mechanism that was displayed upon initial page load.

Legal Reform

The Government has put forward proposals for reform of the cookie rules in its Data: A new direction consultation. In summary, the proposals would remove the requirement for consent for cookies that constitute a low privacy risk, such as first-party analytics cookies. Subject to the necessary safeguards and a clear provision to ensure such cookies cannot be used to track individuals, this would be a welcome change. Many websites that currently use strictly necessary and analytics cookies would be able to then remove their consent mechanisms. Only websites that use intrusive, high-risk tracking and behaviour monitoring cookies would be forced to ask for a visitor’s consent before placing those cookies.

Furthermore, the Government is proposing to bring the enforcement scheme for PECR in line with the UK GDPR. PECR enforcement currently takes place through the old provisions of the Data Protection Act 1998, with the maximum monetary penalty for PECR breaches standing at £500,000. The Government is proposing to change PECR’s enforcement provisions to those of the Data Protection Act 2018 and to increase the maximum monetary penalty for PECR breaches to £17.5m or 4% of global turnover, the same as for the UK GDPR.

Overall, if implemented properly, I believe these changes would be beneficial for both data controllers and data subjects. Furthermore, I believe urgent priority should be given to enable browser-level consent mechanism for cookies to be widely implemented with a set range of categories. This would involve users having to set their cookie preferences in their browser once and websites respecting these settings by default, while allowing the user to override their preferences for individual websites if they wish. Legislation already provides for this, but it requires browser vendors to make the necessary changes and website administrators to integrate their cookie placement with these browser settings. Currently, it is only possible to disable all cookies in your browser settings: this is not appropriate to comply with the consent requirements, as strictly necessary cookies required to make the website work would also be blocked.

Supervisory Authority Enforcement

The ICO has done a good job at writing practical guidance on the cookie rules, published in 2019. The detailed guidance can be found here

It would be useful, however, if the ICO and other supervisory authorities started enforcing in this area. The French CNIL and the Spanish AEPD have recently started with some enforcement action, but it is clear that a concerted, international effort is needed to tackle the problem. Enforcement is currently practically non-existent. The majority of European websites do not comply with the GDPR and ePrivacy Directive rules regarding cookies and this has created a cluttered, hard-to-use and intrusive web browsing experience.

This exacerbates wholly misinformed commentary on the issue, such as the commentary published in the Taskforce on Innovation, Growth and Regulatory Reform independent report, which mistakenly claims that the GDPR is to blame. The contrary is true. Because so many websites do not comply with the GDPR and the ePrivacy Directive, internet users have been tricked into believing all the non-compliant designs are mandated by the GDPR. All the more reason for supervisory authorities to up their game and start enforcing on this issue, something that NOYB is looking to help achieve with their cookie banner campaign.

Enforcement of cookie rules should explicitly include the requirement for consent mechanisms to provide a genuine choice and to be easy to use: just-in-time consent mechanisms for cookies used for a particular function (e.g. user authentication across sessions, ‘remember me’) are rarely used but are sometimes far more suitable than annoying cookie walls upon loading the website. In any case, initial cookie consent modals should be relatively straightforward and provide a clear, genuine choice, with the option of reading more detailed information and making granular cookie category choices if desired. It’s not particularly hard to implement a compliant solution, either: free boilerplate code templates exist.

Civil litigation and the effect of Lloyd v Google

As per Regulation 30 of PECR, Article 82 of the UK GDPR, and S. 168 of the Data Protection Act 2018, data subjects are entitled to claim monetary compensation for damage suffered by reason of a data controller’s infringements of the cookie rules. Such damage includes non-material damage, such as distress, injured feelings, indignation, annoyance, and frustration.

A slightly weaker compensation scheme was in place under the Data Protection Act 1998. This was the scheme under consideration in Lloyd v Google LLC [2021] UKSC 50. It was on this basis that Mr Lloyd claimed compensation from Google for secretly placing tracking cookies on users of the iPhone’s Safari browser. However, Mr Lloyd also sought to claim compensation on behalf of all iPhone Safari users in a new, opt-out style class action claim. Mr Lloyd claimed that all these users had suffered ‘loss of control of personal data’ and were thus entitled to compensation.

The Supreme Court did not agree with Mr Lloyd and declined to allow such an opt-out style class action claim, stating that Mr Lloyd’s claim was not actually seeking to prove that damage had been suffered by reason of Google’s secret cookie tracking. However, the Supreme Court clearly stated that, if Mr Lloyd had individually claimed for the distress he had suffered because of Google’s secret tracking, such a claim would have had a real prospect of success.

This provides some welcome clarification that distress, frustration and other non-material damage suffered by a data subject as a result of a data controller’s unlawful placement and processing of tracking or behavioural advertising cookies on their device is likely to satisfy the de minimis threshold, required to be entitled to compensation. An example of a claim that would not satisfy the de minimis or triviality threshold was given by the Court of Appeal as an accidental, one-off breach of data protection law. In my view, breaches of the cookie legislation are often structural, deliberate, persistent and for the data controller’s commercial gain, rather than ‘de minimis’, accidental, one-off, trivial breaches for which no compensation is due (as some have suggested).

The Supreme Court appears to agree with this principle (as per paras 23 and 105) which legitimises – and will perhaps fuel – individual low-value claims for compensation as a result of non-material damage caused by breaches of the cookie rules. Unfortunately, given the current lack of enforcement on this issue by most supervisory authorities, such individual claims seem to be the only way in which unlawful cookie practices can be effectively addressed by data subjects at the moment. Data controllers would do well to treat such low-value individual claims seriously where they have breached the cookie rules. The best defence against such claims is to comply with the law and indeed the ICO guidance.

One aspect of Lloyd v Google may also have been decided differently if the relevant legislation had been the Data Protection Act 2018 and the UK GDPR. This is because non-material damage is explicitly stated as being actionable and the ‘loss of control of personal data’ is listed as an example of such damage in the recitals of the UK GDPR. Further clarification on this developing area will likely have to be given by the courts in the future.

Closing thoughts

The European web is a mess as a result of widespread non-compliance with the ePrivacy Directive and the GDPR. The status quo is that most people click ‘accept all’ on cookie banners out of frustration with hard-to-read walls of complicated text and design tricks. If people were actually provided with clear information on what these cookies did and were provided with a genuine, equivalent choice as required by law, I would imagine that the majority of internet users would not consent to intrusive tracking cookies used to monitor users’ every interaction across websites and to form a valuable advertising profile of users. This is supported by Apple’s recent ‘Do Not Track’ option in iOS, with around 90% of users reportedly declining to be tracked for advertising purposes having been given a clear, genuine choice on the matter. Apple’s approach also demonstrates the success of providing device-level, global consent settings that all websites can then access and adhere to.

But of course, we are told this would be a blow to the internet advertising and real-time bidding industry worth billions, which partly explains why non-compliant, intrusive practices are still rife across the web: this industry relies on tracking and monitoring you all across the web to profile you and find out things of interest about you. Personally, I would much prefer to be shown advertisements relevant to the content of the website I am visiting rather than being based on a Google search I conducted the week before.

2 Pingbacks