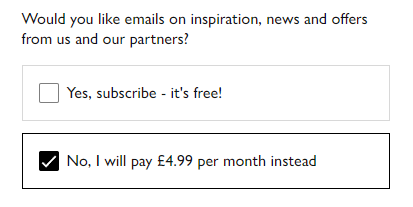

ICO opens call for views on “consent or pay” business models after adtech industry engagement. But allowing this legally flawed concept would have serious consequences in many areas beyond cookies – “accept marketing emails or pay £4.99 per month to refuse” would be on the cards.

The ICO has opened a call for views on “consent or pay” business models: https://ico.org.uk/about-the-ico/ico-and-stakeholder-consultations/call-for-views-on-consent-or-pay-business-models The call for views is open until 17 April 2024. Separately, the European Data Protection Board is also considering the issue.

The ICO’s “emerging thinking” appears to leave the door ajar to incorporating ‘consent or pay’ in its new guidance about cookies. This would be a mistake and make the ICO’s job in enforcing PECR much harder. The ICO must stand firm and reject ‘consent or pay’, which only appears somewhat plausible because of the current status quo of non-compliance regarding consent for tracking cookies. Where legislation requires ‘consent’ to the UK GDPR standard, or the ‘consent’ lawful basis is used, there is no proper basis for charging users to refuse consent in my view.

I have included my responses to the consultation below.

My initial response

I do not agree that ‘consent or pay’ is a lawful option under the UK GDPR and PECR. While it is not expressly prohibited (like many unlawful processing practices), it’s clear that being forced to go through a payment mechanism is not as easy as clicking an accept all button (and would breach Article 7(3) UK GDPR). Any consent given by clicking accept all would also not be freely given in such a case, particularly considering the context where the ICO rightly states that merely having to navigate to a second layer to click reject is also non-compliant. Article 21(2) UK GDPR also provides an absolute right to object to direct marketing processing, including profiling through tracking for such purposes, for which no fee may be charged in principle (see Article 12(5) UK GDPR).

—-

Power balance: Allowing ‘consent or pay’ will likely lead to many organisations implementing this due to the significant commercial benefits this offers them and the adtech industry. A data subject will therefore be forced to fork out significant sums of money for many services they access, just to be afforded their legal right not to have unnecessary cookies placed on their device. The power imbalance in such a situation is so significant that ‘consent or pay’ cannot be what parliament intended by enacting PECR and the UK GDPR. Furthermore, organisations are free to choose what payment methods to accept. Data subjects who do not have access to mainstream credit/debit cards or online banking, or would find using these more difficult, are likely to be discriminated against by any ‘consent or pay’ mechanism. This is particularly likely to be the case for elderly people, who are more likely to use cash or traditional banking services. Additionally, children under the age of 13 are not legally capable of giving consent under the UK GDPR, yet they are likely to click ‘accept all’ when the alternative is that they have to make a payment using a card they are unlikely to have.

Equivalence: In respect of tracking through cookies specifically, PECR is clear that they cannot be placed unless the user consents. The user therefore has the right to access a web service without having unnecessary cookies placed on their device. Being forced to pay for this legal right flies in the face of Parliament’s intention in enacting PECR and subsequently strengthening it through multiple amendments. Of course, a web service can choose to make the content itself accessible only to users who pay a fee (but this cannot be related to placing unnecessary cookies).

Appropriate fee is entirely inapplicable. Data subjects have very strong rights under R.6 PECR (mandating freely given consent that can be rejected/withdrawn as easily as accepting), and Article 21(2) UK GDPR (allowing data subjects to object to any processing for direct marketing purposes). There is no proper basis for forcing data subjects to pay for being afforded these rights. I believe any payment of a fee would likely be recoverable as material damages under Article 82 UK GDPR – the ICO would thereby expose organisations to civil litigation by expressing a view in favour of consent or pay [if organisations were to follow this view].

Privacy by design: A payment system, by design, requires data subjects to give the organisation significant additional information (e.g. card details, payment information etc). Data subjects who do not wish to give websites their financial information, just for their legal rights to be upheld, would therefore face significant barriers in accessing web services. Recital 32 of the UK GDPR also states that consent given by electronic means must not be “unnecessarily disruptive to the use of the service for which it is provided.” It is clear that imposing a payment barrier, by design, would be seriously disruptive to using the service beyond what is necessary.

—–

Beyond cookies, allowing ‘consent or pay’ would have disastrous consequences. For example, when booking a flight, airline operators may offer a ‘tracking-free’ increased fare, or a reduced ‘tracking’ fare where they share all personal details with advertising partners for marketing purposes using the consent lawful basis. As the lawful basis of consent does not have a legitimate interest assessment requirement, controllers can act with far fewer restrictions under ‘consent or pay’. ‘Consent or pay’ would effectively force data subjects to agree to the reduced ‘tracking’ fare for services in all areas of life, unless they are prepared to fork out significant sums of money. ‘Consent or pay’ would likely become ubiquitous across many sectors and many different interactions with users if the ICO expresses a view that it is permitted, given the vast commercial benefits for data controllers.

General consumer law also makes consent or pay completely unviable. Under the Consumer Contracts (Information, Cancellation and Additional Charges) Regulations 2013, consumers have the right to cancel a contract for a service within 14 days. If the ‘non-tracking’ service has been used in that time, organisations will still have to refund the fee proportionate to what is unused.

Regulation 7 of The Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations 2008 prohibits aggressive commercial practices. Threatening to track users and share their data with a plethora of adtech controllers unless they pay a fee is, in my view, likely to amount to undue influence, given parliament’s intention in enacting PECR and the UK GDPR.

Additionally, unnecessary cookies are not exclusively used for behavioural advertising tracking. They are also used to measure the impact of an organisation’s advertising spending and for general analytics purposes for the organisation, services for which the organisation often pays external service suppliers. It would be farcical for organisations to expect data subjects to pay for this, yet allowing ‘consent or pay’ would open the door to such practices.

—-

Users of web services have had the right to browse the web without unnecessary cookies for many years. Now the ICO is finally taking steps to enforce the law. The fact that some web services are only now advocating for ‘consent or pay’ demonstrates the complete disregard many have (had) for the longstanding legislation. The commercial gains that web services and the adtech industry have made by flouting the law over the years are immense. ‘Consent or pay’ must not be allowed to become something through which such organisations can keep circumventing the law by the back door.

Compliant solutions, in my view, include running contextual ads without tracking, or only allowing users to access to full page contents upon payment (i.e. the payment being for accessing the page contents, like a newspaper subscription, and not for doing so without tracking).

—-

The European Data Protection Board (EDPB) is currently also considering the ‘consent or pay’ principle, although many supervisory authorities have expressed a view that it is not possible under the current legislation. The consequences of allowing consent or pay in the UK are likely to be severe. If the harmonised position in the EU is to prohibit ‘consent or pay’, allowing this in the UK would, in my view, likely impact the UK’s adequacy status for the reasons previously given.

None Of Your Business (“NOYB”) also has extensive resources and information available on the dangers of allowing ‘consent or pay’ to which end please see https://noyb.eu/en/28-ngos-urge-eu-dpas-reject-pay-or-okay-meta

My further response: how ‘consent or pay’ would completely undermine PECR’s protections against direct marketing spam

Examining PECR and examples of the consequences of allowing organisations to charge for refusing consent

Regulation 2 of PECR states: “consent” by a user or subscriber corresponds to the data subject’s consent in the UK GDPR (as defined in section 3(10) of the Data Protection Act 2018).

Regulation 6 of PECR requires that a user has given their “consent” before unnecessary (tracking) cookies can be placed. However, ‘consent or pay’ would provide an option for organisations to force data subjects to pay before they can refuse to consent. This would clearly be unlawful under the UK GDPR and PECR for the reasons stated in my previous response.

However, there would be further serious consequences if ‘consent or pay’ were to be valid, because R.6 PECR uses the UK GDPR definition of consent that many other provisions also use. As such, if (hypothetically) organisations could charge users to refuse consent to tracking cookies, they can logically also do so for other processing purposes.

Regulation 19 PECR prohibits automated marketing calls without a subscriber’s consent. If ‘consent or pay’ were to be allowed, an organisation could, for example:

- During a signup process, state that they want to use a data subject’s phone number for making automated marketing calls, offering the user an accept and reject option;

- Allow the data subject to select the ‘accept’ option free of charge;

- Charge the data subject a sum of e.g. £3 per month to refuse consent.

Data subjects that consent to automated marketing calls are likely to make the organisation more money than those who reject. Similarly, users who accept tracking cookies may make an organisation more money than those who reject. Therefore, under ‘consent or pay’, the organisation would be justified in charging users to refuse consent, like they would be in the context of tracking cookies.

Regulation 21B PECR prohibits marketing calls of pension schemes without a subscriber’s consent. If ‘consent or pay’ were to be allowed, an organisation could, for example:

- When a user signs up for a personal pension scheme website, allow the user to accept or refuse marketing calls for the pension scheme;

- Allow the data subject to select the ‘accept’ option free of charge;

- Charge the data subject a sum of e.g. £5 per month to refuse consent.

Data subjects that consent to marketing calls for personal mension schemes may make the pension organisation more money than those who reject. Similarly, users who accept tracking cookies may make an organisation more money than those who reject. Therefore, under ‘consent or pay’, the organisation would be justified in charging users to refuse consent for pension marketing calls, like they would be in the context of tracking cookies.

Regulation 22 PECR prohibits the sending of marketing emails to individual subscribers without consent. If ‘consent or pay’ were to be allowed, an organisation could, for example:

- When a user signs up for a forum, allow the user to accept or refuse marketing emails from the forum’s advertising partners;

- Allow the data subject to select the ‘accept’ option free of charge;

- Charge the data subject a sum of e.g. £10 per month to refuse consent.

Data subjects that consent to marketing emails from the forum’s advertising partners are likely to make the forum more money than those who reject. Similarly, users who accept tracking cookies may make an organisation more money than those who reject. Therefore, under ‘consent or pay’, the organisation would be justified in charging users to refuse consent for marketing emails from the forum’s advertising partners, like they would be in the context of tracking cookies.

Regulation 22 PECR, the soft opt-in and the “free of charge” requirement

Regulation 22(3) of PECR provides a favourable alternative to obtaining consent for organisations (the “soft opt-in”).

Regulation 22(3)(c) states as one of the requirements of the soft opt-in: “the recipient has been given a simple means of refusing (free of charge except for the costs of the transmission of the refusal) the use of his contact details for the purposes of such direct marketing, at the time that the details were initially collected, and, where he did not initially refuse the use of the details, at the time of each subsequent communication.”

It is therefore clear that a refusal by a data subject must be free of charge, even as part of the soft opt-in which is favourable to organisations. However, if ‘consent or pay’ were to be allowed, the soft opt-in would in fact not be favourable to organisations at all, as, under consent, they would be able to charge data subjects a fee to refuse. This clearly would render the soft opt-in effectively useless and cannot have been Parliament’s intention.

Furthermore, under both the purposive and teleological legal interpretation approaches, it is clear that the ‘free of charge’ requirement for refusing under the soft opt-in also applies to consent generally.

Consent or pay’s logic is legally flawed but made somewhat plausible by the current status quo of non-compliance in the context of consent for tracking cookies

The law requires an organisation to obtain (freely given) consent for certain processing, but the logic of ‘consent or pay’ is that a user should have to pay to refuse if an organisation can earn more money if a user accepts. With the adtech industry and many organisations being accustomed to their extra, unlawfully obtained income by failing to obtain consent before using tracking, they would clearly love to maintain this status quo by charging users to refuse. However, this is a hugely distorted reality from what the law says. Legally, the status quo should be that no tracking takes place at all, unless and until a user freely accepts. This was clearly parliament’s intention in enacting PECR and the UK GDPR. If parliament had wanted to make changes, it could have done so in the DPDI bill (but notably has not done so, excluding behavioural advertising from the loosened requirements under R.6).

The same applies to all the above examples: no direct marketing emails/automated calls etc should be sent unless the user freely consents. The logical legal consequence of ‘consent or pay’ is that organisations can charge users to refuse their marketing communications. This demonstrates the complete absurdity of ‘consent or pay’, but would be a very real consequence of the ICO entertaining ‘consent or pay’ in its regulatory stance. It would be a huge mistake and would cost the ICO dearly in its effective enforcement of PECR in areas beyond cookies. The ICO should stand firm and tell the adtech industry (who appear to be pushing for consent or pay to be allowed) the obvious: consent or pay is forbidden. The ICO’s purpose is to enforce the existing legislation.

2 Pingbacks